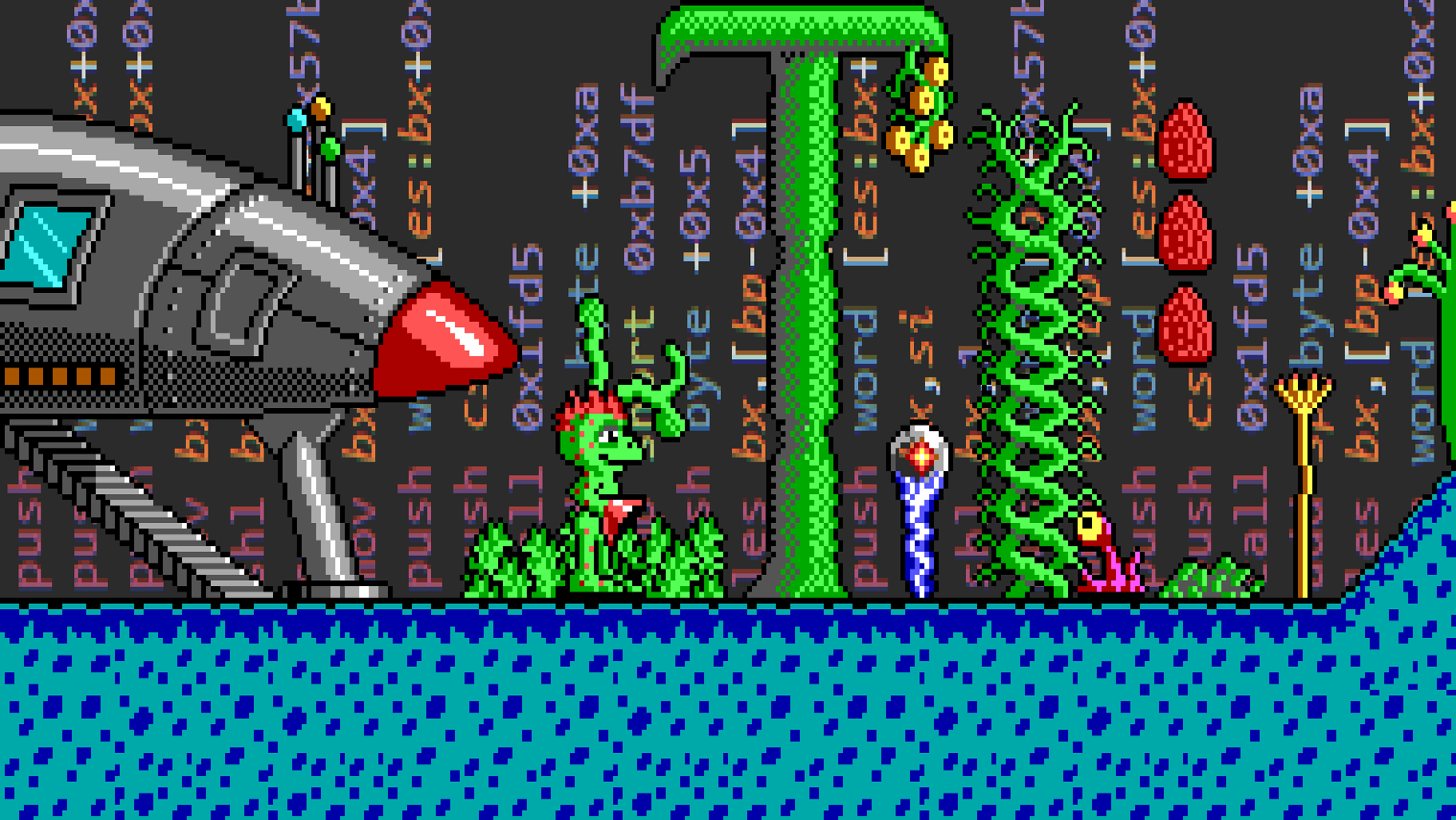

Cosmore

Cosmore is a reconstruction of the source code of Cosmo’s Cosmic Adventure, a DOS game originally released in 1992, using the original C compiler and x86 assembler from 1988. The project involved disassembling the original game files, analyzing their structure, and producing new C and assembly code that best approximates what was written by the original authors almost three decades prior. In addition to making the game run and play accurately in its native environment, particular focus was placed on truly understanding the purpose of each function and variable, naming and commenting each one as appropriately as possible.

Cosmo’s Disassembly Adventure

This has been a massive project, made even more difficult by using an arcane compiler in an unfriendly operating system. In spite of the challenges, the reconstruction now produces an executable file that performs exactly like the original game. With the exception of a few inconsequential differences in the internal memory layout, the reconstruction is identical to the original.

In total, Cosmore took almost five years to produce, with a few false starts and breaks along the way. The project originally started in January 2016 as an attempt to figure out how the parallax backdrops were drawn on the under-powered Intel 286 processor. That led to a deep dive into the game files, trying to extract the image data and figure out how it was encoded.

In April 2017, I started to shift my focus to the game’s executable file, searching for the code that made use of the image data that I had extracted. I had never really worked with x86 assembly before, especially not in a 16-bit DOS environment, and the modern tools I was using were rather unintuitive for the task. I took a detour to learn more about assembly programming for these primitive processors.

By September 2018, I had written a custom disassembler from scratch, with a few annotation capabilities to help me reason about 16-bit memory addressing. This was a major help, especially because I was still a novice at reading x86 code. Armed with this tool, and everything else I had learned along the way, I was ready to seriously begin the process of disassembling and searching the game’s executable file for the relevant drawing functions. I traced through each function, trying to assign meaning to meaningless code and data addresses, writing out notes in a kind of hybrid C/Python pseudocode that made perfect sense to me and only me.

In January 2019, I made the choice to start translating the pseudocode I was looking at to valid C. This was done partially because it was easier to read, but also because I wanted a way to make changes and experiment with the code and see how the images on the screen responded. I knew that the original game was compiled with Borland Turbo C, and it wasn’t too terribly difficult to track down a copy and get it to run in DOSBox. Without realizing it at the time, I had started to lay the groundwork for what would become Cosmore.

It only took about a month to translate all of the pseudocode to C. I had traced and reimplemented so many different areas of the game that really the only things missing were the enemy actors and a few interactive bits. Since I had come so far, I spent another additional month disassembling and rewriting all of the remaining features across all of the retail episodes. On March 1, 2019, all three episodes could run and be played through in their entirety under Cosmore.

That was all well and good, but I didn’t actually understand the things I wanted to understand. Most of the variables and a few of the functions had completely opaque guesses for names, and the code I had produced was not really well structured. To make matters worse, I was finding translation errors that were causing bugs and crashes in the game. My code wasn’t behaving fully like the original, which meant that anything I learned from the Cosmore code might not actually reflect the way the original game worked.

Starting in December 2019, and for about eleven months after, I compared every instruction in Cosmore to every instruction in the original game, looking for differences in the machine code and trying to figure out how to change the C code to make the compiler produce the same output. In some ways it made the code uglier—the original authors did some highly disagreeable things that I personally would’ve changed, but I was bound by my quest for parity.

On October 26, 2020, I located the last translation error: a misread keyboard scancode in a debug feature that I don’t think anybody else even knew about. The games were now identical. I spent some time cleaning up a few more variable names and comment blocks, squashed my miserable Git history, and opened the repository to the public on November 7, 2020.

I’m not done with it just yet. The goal is to eventually write a complete technical manuscript about all aspects of the game’s workings, similar to Fabien Sanglard’s Wolfenstein 3D and Doom Game Engine Black Books. This ongoing effort is called Cosmodoc.

« Back to Projects