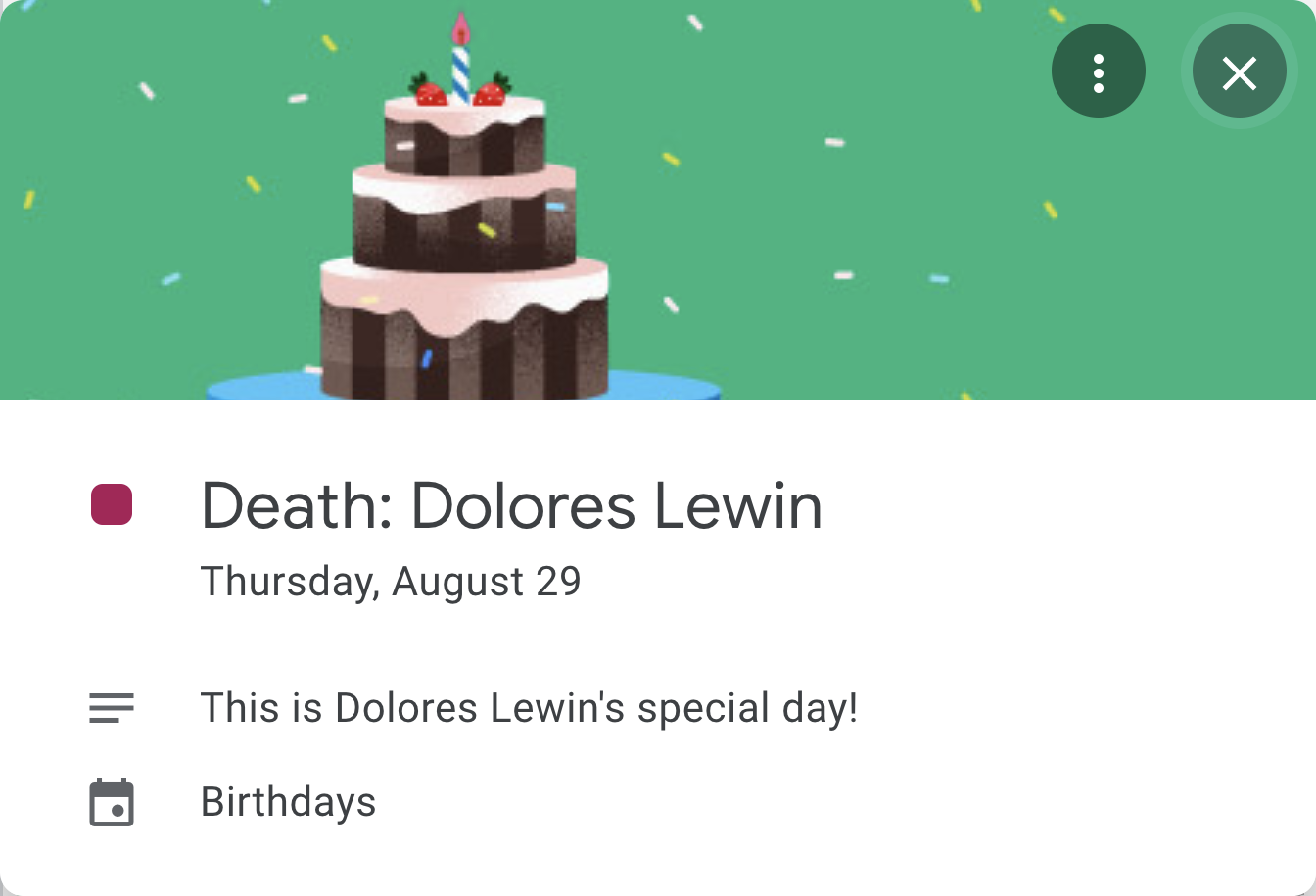

This is [my dead grandmother]’s special day!

Update (January 2025): A reader reached out to inform me that Google recently revamped the graphics and placeholder text in their Calendar product, which either directly or indirectly fixed the condition that this article describes. Still, this issue existed for long enough and produced a screenshot that was absurd enough to warrant preserving here.

When you get right down to it, there is really only one thing that we can all predict with absolute certainty: We are all going to die someday. Each and every person you have ever met will either outlive you or be outlived by you. Barring some freak accident or staggering coincidence where you die simultaneously. I lead with this wholly dour introduction to really drive home how difficult it can be sometimes to voluntarily think about such things even though they are absolutely going to happen to you, me, and everybody.

Obviously it’s a good idea to plan for this preordained eventuality. There’s already plenty of advice out there on the business of death and how to best plan for it. That’s not what I’m going to talk about here. This article is about little things some might do after the funeral.

Grief and data retention policies

Take a look through the list of contacts in your phone’s address book. It’s pretty much exclusively alive people, right? What happens when circumstances change, though? Say you now have somebody in your address book that has died. What should happen to that entry? The pragmatist might say to delete it; it’s not like you’ll be contacting each other again.

The problem with deleting an address book contact is that it tends to wash that person’s identity off past communications. Remove a name, and their old text message thread reverts back into that second class number-only pile next to all the political messages and login verification codes. If you want to keep the messages (or voicemails, or perhaps emails) while retaining the human aspect of the person who sent them, you’ll want to save the contact. This is more in line with what a sentimental (or lazy) person might do. (Or avoid doing.)

If the contact entry is retained, which of its fields should be kept? Obviously the phone number and/or email address, as that’s what allows it to be linked to the intended messages in the first place. The name and contact photo should stay; that’s part of the identity you want to preserve. It wouldn’t be a crazy idea to hold onto the street address in case you ever wanted to reminisce and find their old place on Street View or whatever future exploration tools the world invents. The birthday should probably stay so it can serve as a nice little annual reminder of their life in your calendar. Hell, maybe the whole contact should be preserved in its original form. Not only does it provide useful identity context to past conversations, but it can serve as a mini-memorial too.

But how does this affect me?

I decided some time ago that my policy would be to keep the contact entries of dead people without clearing any fields. Sure, somebody new will eventually move into their house, and some other customer will scoop up their old phone number, but I don’t consider either of those to be a practical concern. If a situation arises where I need to swap a dead person’s phone number onto the contact of an alive person that I know, I would take that as a sign to buy a lottery ticket. And as for address conflicts? Well hey, looks like old Uncle Al got himself a housemate.

In addition to preserving all the existing fields, I also add the date of the person’s death as a “significant date” on the contact, just to help remember it.

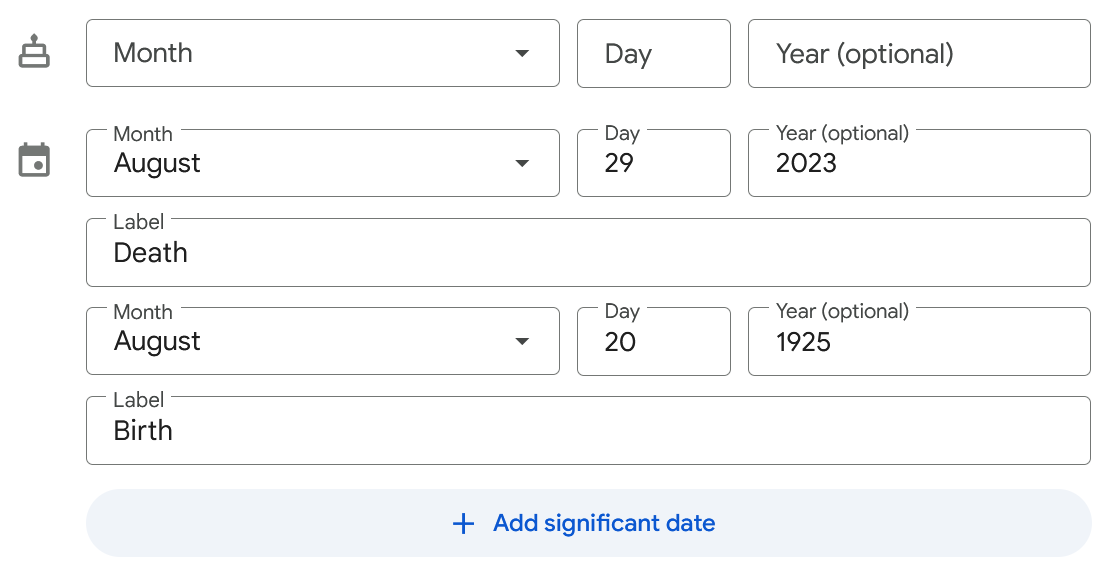

Last summer, my grandmother died. She had just turned 98 and, quite frankly, she had earned her eternal rest after all those years. In the days that followed, I did what I do and adjusted her contact to commemorate the dates. The fields ended up looking like this:

The significant dates on my grandmother’s Google Contacts entry. My convention is to move the birthday into a significant date named “Birth” and the date of death into “Death” alongside it.

I’ve been using Google for email for close to twenty years, and continue to use it mainly out of habit. And sheer migration difficulty. And laziness. Due to the tight integration between services, I also use Google’s Calendar and Contacts products. Google maintains the primary copy of my contacts list, and all the devices I use on a day-to-day basis synchronize with that. As a result, my grandmother’s contact—her mini-memorial—lives in Google.

Baffling product decisions

Google contacts have two kinds of date fields: Zero or more of the aforementioned “significant dates” and one “birthday,” which can be left empty. For contacts with a birthday specified, those dates are collected into a calendar called Birthdays This calendar is identified internally using the ID “addressbook#contacts@group.v.calendar.google.com.” over on the Calendar product. Google takes care of updating and maintaining these events based on updates made to the contacts, which is actually rather convenient.

So contacts may have a birthday, and this date is dynamically entered into the Birthdays calendar. That’s just fine. And those other significant dates, do they appear anywhere?

They go into the Birthdays calendar too.

I mean, I guess I can sorta understand how a product could grow and evolve into a state where it has some incongruities, and I suppose it’s understandable that maybe the Birthdays calendar might have been more aptly named “Birthdays and Significant Dates” in hindsight. That’s excusable. Generating a name for the significant date’s event using the pattern “[significant date label]: [contact name]” makes sense too. I think we’re probably fine here.

I guess the road to inadvertently awful product voice is paved with good intentions.

Life is messy

The fields on these contacts are called significant dates. Not happy dates. Not celebratory dates. The contact’s exported vCard uses the completely neutral name itemN.X-ABDATE/ABLabel and the CSV files call them Event N - Value/Label. Nowhere in any of the file format specifications does it prescribe that “special day!” is the appropriate messaging or that a three-layer chocolate strawberry cake powdered in confetti is the best image to accompany such an event.

There are all kinds of things a person might want to commemorate. Some, like birthdays and anniversaries, are happy occasions. Not everything is. Some people might use these fields to remind them of something somber or sad. The date a person went away. The date somebody went through something unthinkable. A date on which one chapter closed, and a significantly different one opened. Just because we choose to remember a date doesn’t automatically mean we want to be happied at each that date recurs.

There is actually an entire goddamn RFC that adds DEATHDATE and DEATHPLACE to the list of properties that can be stored in a vCard, This document was published twelve years ago and yet I’ve never seen any mention of it—much less an actual implementation in a user-facing product—prior to writing this article. although Google Contacts does not seem to understand how to import or preserve them.

Computers are as dumb as we tell them to be

The reason this happens is because somebody dictated that it should happen. Somebody looked at the birthdays and significant events and said “we need to fill this empty space.” Somebody made a decision that, no matter what the context, a cake image and a bunch of perfunctory nothingness about a “special day” was what was called for. And on a product that goes as far as to show a toothbrush and dental floss on any calendar event that looks like it might be a dentist appointment, In fact, the Google Calendar web app has a whole bunch of event-specific images. If an event has a keyword like “coffee” or “lunch” it will show a moka pot or a full plate of salad. Events mentioning “baseball” show home plate with a bat and ball. “Movie” yields a big popcorn tub. One website has amassed a list of 57 event types that Google Calendar looks for to apply these illustrations. no less!

And yet, all that goes out the window for events that come in through significant dates attached to a contact. It’s not like it takes an artificial neural network to figure out whether or not a calendar event references the word “death”—that could be done using strstr() or any number of library functions built atop it over the last half a century. And the state of computational linguistics is sufficiently advanced that one could ask, Hey, is “fiancée’s Afghanistan deployment” a happy thing y/n? and get a pretty decent guess. Google just… doesn’t.

It’s somehow both surprising and utterly predictable that a company of nearly 200,000 employees could ship a feature whose empty corporate geniality ends up conveying a worse sentiment than if they had just left the damn space blank. It really comes across like one of those amateur-hour oversights that somebody really ought to have considered, if only briefly. Brief consideration is all it should’ve taken to realize how easily something like this could occur and how absurd it would look.

In a way, I think this stems from a mostly manufactured problem that product people and UI/UX designers feel like they need to solve. “We have an opportunity to show something, we can’t not show something!” It was happening way back in desktop computer software in the 90s, some of which would start up with some form of wizard because I guess simply presenting the user with an empty window would scare them away and they’d never use the software again, despite having already paid handsomely for it.

It really feels like these designers have an aversion to empty space on the screen, so they fill it with… bullshit. That’s really the only word that aptly describes it: Pointless, valueless, thoughtless, space-occupying bullshit. But slinging bullshit is a double-edged sword, because there’s always the risk that the bullshit isn’t perfectly appropriate for the space it’s occupying. Sometimes it’s flagrantly inappropriate. Laughably inappropriate.

So let’s all enjoy a slice of Google’s delicious bullshit cake. My grandmother is dead, after all.

« Back to Articles