The Mannheim Steamroller Version of “Deck the Halls” Is Insufferable and I Will Fight Anyone Who Disagrees

“Deck the Halls” is a Christmas carol whose lyrics, penned in the late 1800s, describe traditions and celebrations of the Yule—not Christmas!—holiday. The music is perhaps centuries older, repurposed from a Welsh song called “Nos Galan” and associated with New Year’s gift-giving (the English translation of the title literally means “New Year’s Eve”). The combined music and lyrics have been covered by innumerable artists who have each added their own flair to the performance, but the essential spirit of the song is always the same:

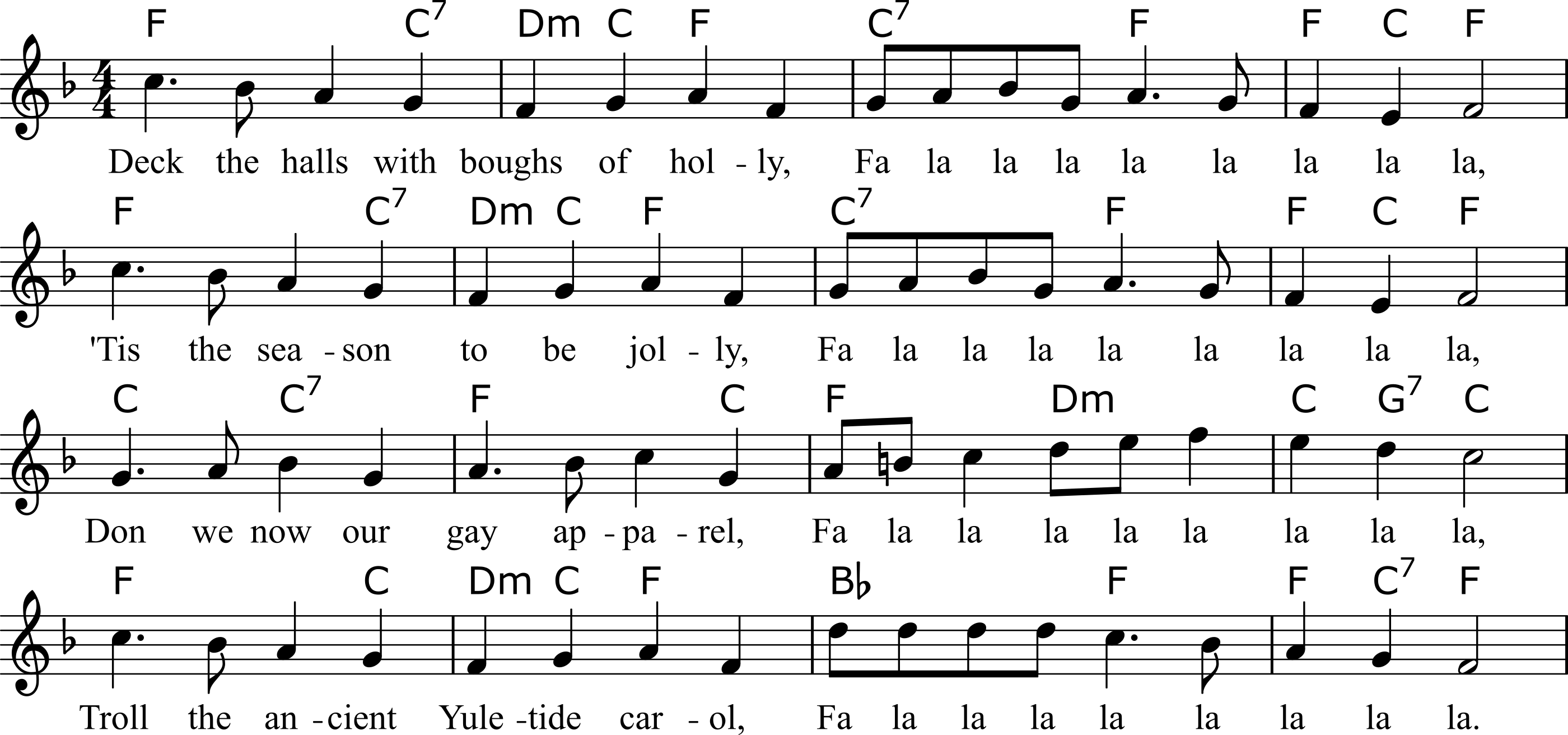

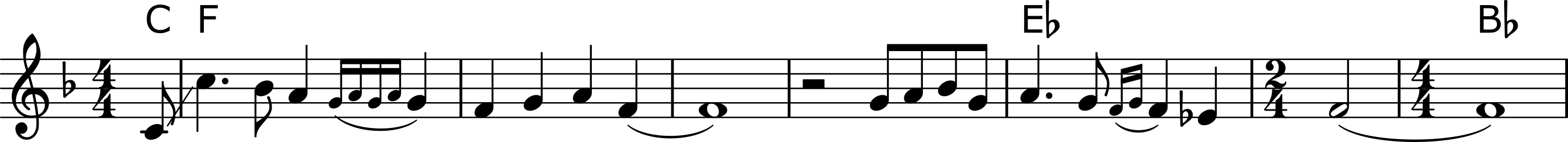

![“Deck the Hall [sic] With Boughs of Holly” as printed in The Pennsylvania School Journal, vol. xxvi (1877, Wikipedia). This version lacks the third set of “fa la las” and their distinct melody.](/articles/mannheim-steamroller-deck-the-halls/deck-the-hall-1877.jpg)

“Deck the Hall [sic] With Boughs of Holly” as printed in The Pennsylvania School Journal, vol. xxvi (1877, Wikipedia). This version lacks the third set of “fa la las” and their distinct melody.

The original song is a straightforward jaunt in “common” (4/4) time in the key of F major. It was apparently first recorded for wide distribution by Bing Crosby in 1949, and because hoo boy do baby boomers love Christmas music, multiple artists throughout the 1950s and 60s have found success with their own versions. It’s not uncommon to encounter the song sung by Percy Faith And His Orchestra (1954), The Ames Brothers (1957), Kate Smith (1959), The Everly Brothers (1962), or The Ray Conniff Singers (1962).

Mannheim Steamroller is an American music ensemble (whose name is a riff on the Mannheim Roller) This is the sort of wordplay that Niles Crane might sneer towards Frasier, eliciting from the studio audience the sort of laughter that comes entirely from the actor’s delivery as opposed to understanding why any of those words form a joke. originally formed by songwriter/multi-instrumentalist Chip Davis and pianist Jackson Berkey. You might already be familiar with Davis’ prior work without even realizing it: In the 1970s he co-wrote the song “Convoy” by C.W. McCall, for which he won SESAC’s “Country Music Writer of the Year” award in 1976. In fact, a surprising number of musicians on Mannheim Steamroller’s 1984 Christmas album—aptly named Christmas—also played on Black Bear Road, the album that “Convoy” headlined.

The first track on Christmas is titled “Deck the Halls” and, as one might surmise, is yet another rendition of the well-known carol. It is an instrumental piece with prominent synthesizer, french horn, and strings. As best I can determine, the intention of the song is to reimagine the traditional tune—which, remember, is centuries old—by marrying classical music techniques with cutting-edge-at-the-time popular music production choices. The result is basically what you would expect: “Deck the Halls” on a bunch of synthesizers.

The song may have originally found its foothold in the U.S. due to its many appearance on conservative talk radio. Rush Limbaugh played Mannheim Steamroller’s Christmas music during his show And now he’s dead. Really makes you think. as sort of an annual tradition, which does sort of line up with the age profile of those who seem to genuinely like it. (And to those who genuinely like it, I feel I must ask: Could you name another Mannheim Steamroller song aside from “Deck the Halls” that you remember hearing? And liking?) (If you answered “Carol of the Bells,” are you sure it’s the Mannheim Steamroller recording, and not Trans-Siberian Orchestra?) At the other end of the spectrum, now there are kids growing up who enjoy the whole aesthetic of the 1980s and unironically listen to this song precisely because of its retro production. It remains a staple of amateur home holiday light shows, Laserium performances at the local planetarium, and as a solid demonstration track for freshly unwrapped hi-fi audio equipment. In other words, “dad stuff.”

Instead of being thrown onto time’s scrap heap along with the Dodge Rampage, Walter Mondale, and the Louisiana World’s Fair, this song is somehow still being played. Every December, and sometimes even in late November, some grocery store or dentist office waiting room plays it. They’ll play it again next year too, I’m sure of it. Against all odds, a synthesizer version of “Deck the Halls” has managed to permanently embed itself in our collective holiday consciousness.

I really despise this song, and I’m going to tell you exactly why.

Just enough scale theory to hurt ourselves

Almost all mainstream Western music is based around a diatonic scale, which is an ordered sequence of seven unique notes. The first note of the scale is the key note, and each successive note in any diatonic scale must maintain a specific distance from the one that came before. In our key of F major, these seven notes are F, G, A, B♭, C, D, E, and after this seventh note we arrive back at F in the next-higher octave. The five notes that were not listed—G♭, A♭, B, D♭, and E♭—are not in the key of F major and should typically be avoided.

I say avoided rather than a stronger word like forbidden because there are occasionally uses for notes that are not in the key. Done properly and used in an appropriate context, it’s possible to use some of these notes to set up a sense of tension or anticipation of something that has not yet come, and many songs have used them very well. Even the traditional arrangement of “Deck the Halls” uses an out-of-key note for a moment. Pop quiz: Are you able to point out where that happens?

One-note-at-a-time is boring, so let’s invent chords. The simplest chord we might play consists of three notes, selected by starting at some position in the scale and including every alternating note encountered while ascending that scale. We don’t want to play two notes that occur right next to each other in the scale, since they sound too similar and tend to clash. Starting from F, the notes of our first chord position (which we’ll identify with a roman numeral I) are F, A, and C. We can keep going up the scale in a similar “every-other-note” fashion:

- II position: G, B♭, D

- III position: A, C, E

- IV position: B♭, D, F This F, and the notes that come later, could either be in a higher octave or “wrapped around” back to the lower starting note. It works either way!

- V position: C, E, G

- VI position: D, F, A

- VII position E, G, B♭

- Back to the I position: F, A, C

This feels straightforward enough, but there is some weirdness in what we have done. Because there are twelve notes on the instrument, but we skip five of them when making a diatonic scale that sounds pleasing, the skipped notes are not able to be distributed perfectly evenly. As a result, in the I position, the top note (C) is seven steps away from the bottom note (F) on the keyboard. But in the VII position, the B♭ is only six steps above the bottom E. The middle note in each chord position also suffers from a similar effect: In I, IV, and V, the middle note is four keyboard steps above the bottom note. In II, III, VI, and VII, the middle note is three steps above the bottom note.

The effect of this is that the chords sound different from each other, and not just because the notes are all getting higher. The varied distances between notes within the chord produce a different audible effect. The pattern used by the four-step chords (I, VI, and V) is said to be major, while the three-step chords (II, III, and VI) are called minor. The names “major” and “minor” actually should more properly be called “large” and “small,” describing the distance between the bottom and middle notes in the chord. In the original ancient Greek, that’s probably what they actually meant. The VII chord, while having a three-step interval that conveys a minor feel, also has a smaller top note interval than all the others. The word for that kind of chord is diminished.

Pulling back to the context of the F major scale, the sequence of three-note chords available to us is F major, G minor, A minor, B♭ major, C major, D minor, E diminished, and back to F major. These are the workhorse chords, and while it’s certainly possible to add additional notes from the scale or even some of the discouraged notes from unrelated keys, you’ll find that, most of the time, most popular and folk music doesn’t. Does the traditional “Deck the Halls” adhere strictly to this palette of chords? Are you sure about that?

The roman numeral notation introduced above can actually be extended to represent the chord qualities: Capital letters for major, lowercase letters for minor, and the addition of “o” to indicate diminished. Some texts use “dim” or “♭5” to indicate this kind of diminished chord, and you should be aware that there can sometimes be some ambiguity that can arise from these different abbreviations. Using this notation, the sequence of chords is I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, viio. Using this kind of shorthand can really help distill music down to its bare essence. Instead of having to explicitly list out the notes (e.g.) B♭–D–F, one could just say “IV chord” and, knowing the key the song is in, reconstruct the list of notes whenever needed. It certainly makes it easier to transpose things into different keys.

Something to dance to

As far as rhythm is concerned, everything really comes down to either halving or doubling things. Occasionally thirding or tripling.

When considering a larger work built from verses containing lines, the music is further divided into a sequence of measures or bars. Any note that lasts for a complete measure is called a whole note. A note lasting for half a measure is a half note. Half as long, there’s the quarter note. The pattern continues for eighth and sixteenth notes as well, but anything much smaller is uncommon. The length of a note is directly related to its frequency—a whole note can occur once per measure, a quarter note four times, and a sixteenth note 16 times. Mixing and matching different-length notes within a measure or group of measures produces a whole bunch of rhythms. Sometimes the rhythm patterns begin on a measure boundary, and sometimes they don’t.

Separate from all that, we have the concept of beats. There is not a strict convention about what a beat is, but you can usually think of it as the “toe taps” or “metronome clicks” of the song. The most popular configuration is to have the beats match up with the quarter notes, resulting in four beats passing for each measure of the song. Half notes last for two beats, eighth notes each last for half a beat, and so on. Four sixteenth notes pass during each beat in 4/4. When we say that a song is in “4/4” time, that means there are four (top number) occurrences of a quarter (bottom number) note in each measure. If the tempo of such a work were described as “120 beats per minute,” it would have an equivalent of 30 measures per minute.

It’s common to see chord changes occur on a measure boundary, but it’s not mandatory. Musical phrases and rhythmic patterns tend to align themselves at fixed-count measure intervals. In the traditional “Deck the Halls,” for instance, the alternating pattern of lyrics and “fa la las” repeats every four measures. The overall structure of the verse repeats every sixteen measures. This sort of repetition and internal consistency helps keep a song memorable, but overdoing it can make things feel simplistic.

Distilling the traditional “Deck the Halls”

It’s not always easy to attach chords to works that were not originally written around them. All of the historical sheet music I was able to locate is written for vocal harmony, where each person in a group has a separate melodic line to sing. Together their notes intermingle in curious ways that evoke the sensation of chords but without being bound to that mindset. To interpret these harmonies as chords, one gets a lot of rapid switching between e.g. I and V, sometimes with added notes from the seventh scale degree or a quick flash of a minor chord that’s not really there.

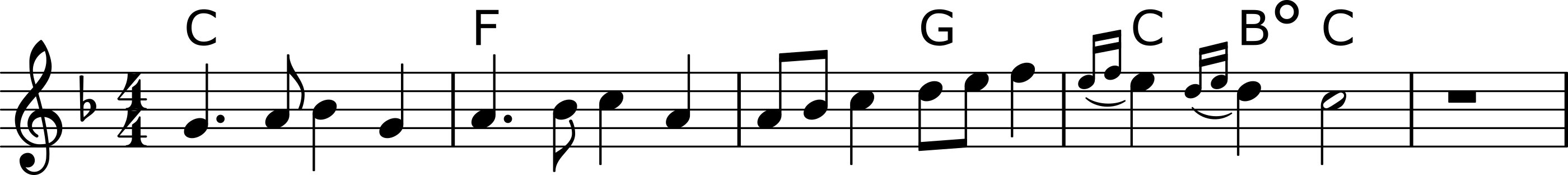

A particularly fancy arrangement of the traditional “Deck the Halls” might look like the following:

Representative arrangement for a modern rendition of “Deck the Halls” that maintains the essence of the traditional song. (LilyPond source)

Admittedly there is a lot going on with the chords marked above the staff, but most of it follows a pattern: Like a winter break–ruining report card, it’s mostly F’s and C’s. The “F” represents the F major chord or the I. Likewise the “C” is a C major or V. “C7” is the same as C major but with the addition of a note seven steps above the chord’s root note (in this case, that seventh note is B♭). This is notated in roman numerals as V7.

Throughout the song, the scale’s key note of F is the anchor point that everything else revolves around. The I chord, having the same root note as the scale, conveys a strong sense of resolution—it is very much the “home” chord. The second-most common chord is the V, which could be thought of as a sort of “going to the office” chord—it’s different but basically familiar. The song travels from I to V and from V to I and it’s all pretty much routine. The addition of the seventh scale degree in the V7 chords creates added anticipation for the upcoming I. Maybe it’s the Friday before a holiday weekend.

The “Dm” (D minor) chord represents the vi, one of the most commonly-found “dark” or “sad” chords in folk and popular music. “Deck the Halls” is not a sad song, nor does it even have moments of plaintive contemplation. When this chord appears here, its primary function is to break up whatever comes before the subsequent V. Another rare chord in this particular arrangement is the “B♭” (B♭ major) or the IV. Its usage in this song could be described as “triumphant” and its unique quality seemingly only fits in with the climactic “fa la la” in the final line.

This leave us with “G7” (G major seventh) which is a weird chord to find here. The notes that comprise this chord are G–B–D–F. Not B♭… B natural. This chord explicitly uses a note that does not belong in the F major scale, producing a chord that does not really belong there either. The roman numeral notation for this one would be II7. This chord follows an earlier appearance of a B natural in the preceding measure, a kind of hint that this was coming. Why is it okay here? The one sentence explanation is that—for just a moment—the chord progression switched to the V with such immense force that it jostled the entire song out of the key of F and into the key of C, permitting notes and chords from that scale to be used. The key of C major contains a B natural note, and a G7 chord is not out of place in the context of that scale. But the far simpler answer is this: It happens because it does. It’s simply part of the composition and it’s always been there. It’s nestled in the middle of a melodic turn that only occurs once briefly in each verse, and it does not overstay its welcome. You’ve probably heard it a hundred times without consciously noticing.

That’s an important thing to keep in mind: It doesn’t matter if an unexpected note or out-of-place chord finds its way into a piece of music so long as it works in the context where it appears. Or barring that, as long as there is some kind of artistic justification for making that unconventional choice. Put another way, the “safe” notes of the diatonic scale and the chords that can be built from them all fit together beautifully, but sometimes a pinch of je ne sais quoi can work wonders.

Another brick in the hall

Repetition is the key to memory. As a consequence of repetition being the key to memory, folk and traditional songs tend to follow predictable patterns. The lines each tend to have identical or substantially similar melodic and rhythmic content, I’m sure somebody out there has had an exchange similar to this during a performance: “What’s the next line… I can’t remember! Something that rhymes with holly. Oh! Jolly. ‘Tis the season, yeah, I got it now.” and even the rhyming nature of one line relative to another could arguably be viewed as a memory aid. The image of the score shown earlier was specifically aligned so that each line of the verse started and ended on a self-similar piece of music. This can be drawn even more explicitly:

Brick chart of the traditional “Deck the Halls” lyrics.

Read horizontally, these are the lyrics with dividing lines between each measure. Vertically, each cell shows a sequence of words with a similar syllable pattern, a common melody, and—in certain columns—rhyming elements. Similar cells can be swapped without really breaking the rhythmic flow of the song, although the meaning of the words could obviously get jumbled.

This works for the chord changes as well:

Brick chart of chords for a plausible “Deck the Halls” arrangement.

We can observe in a similar way that the first two lines of the song are identical from a chord standpoint, and the fourth line is substantially similar to them (essentially only swapping select instances of V and V7, plus the special climactic IV moment).

Take another moment to study these little bricks. Notice how they fit together, and how their internal patterns duplicate themselves into larger constructions. Repetition is the key to memory.

Anyway, here’s Steamroller

The Mannheim Steamroller cover of “Deck the Halls” contains three not-exactly-complete verses of the traditional carol. The first verse starts 30 seconds into the recording, with the first two lines played on a Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 synthesizer with numerous flourishes throughout. The final two lines of this verse are skipped over. The second verse begins, this time on a French horn, at about 55 seconds into the recording. The Prophet-5 returns to complete the last two lines of that verse.

Following this is a passage that has nothing to do with the original song, and which frankly sounds like what would happen if Electric Light Orchestra were commissioned to write a Star Trek theme. This portion of the song is not discussed in this article.

At 2 minutes and 30 seconds, the third verse is played by a string ensemble. This verse is abbreviated; only the first and fourth lines are played. The verse ends on an F which is sustained indefinitely until the recording fades out.

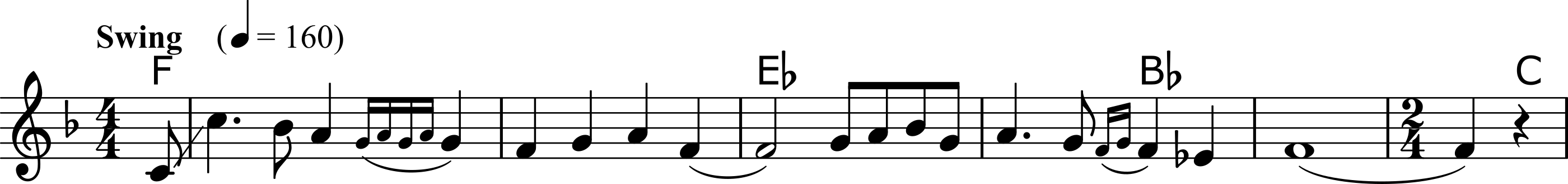

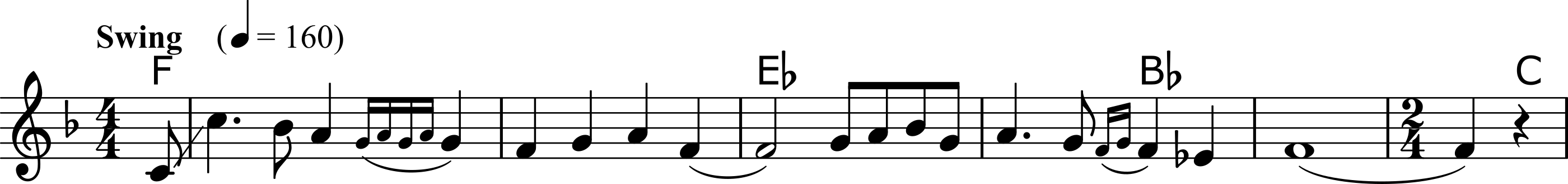

The song could be described as either a 4/4 piece using a “swing” feel, or as a 12/8 piece with a strict preference for the first and third triplets on each beat. Regardless of the notation (I chose the former) the interpretation is the same: The beats follow a “one-and-a two-and-a three-and-a…” pattern where the center “and” is avoided. Of all the liberties taken with this interpretation of the piece, the use of swing rhythm is actually nowhere on my list of grievances. I dig it, and I mean that sincerely.

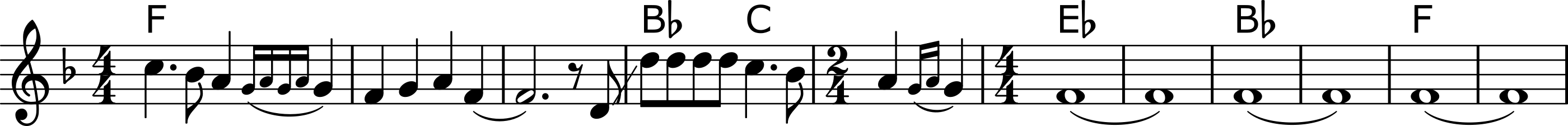

Deck the halls with boughs of holly, Fa la la la la la la la la. (LilyPond source)

Pitchwise, this is substantially the same as the traditional melody. Setting aside the extra ornamentation, only one note sticks out: The E♭ immediately preceding the final note. And that one sticks out like the sorest of thumbs. It’s not subtle, it does not ease the transition from one chord to another, it’s audibly dissonant, and honestly it just seems like it is here out of pure spite.

E♭ has nothing to do with the key of F major, as evidenced by the fact that it requires an explicit flat symbol right next to itself on the staff. It is the flattened seventh of the scale, and is not used in any of the typical chords found in F major. And speaking of chords, did anybody notice the E♭ major chord in the middle of the line? That would be a ♭VII chord in this key; what the actual hell is that doing there?

Careful, he’s in one of his modes again

Make no mistake, the notes we hear are the notes that were played, and the names given to them in this analysis are accurate. No amount of hand-waving is going to change how it sounds and how it makes a listener feel when it occurs. But let’s invent a justification for what is being done with the E♭ here.

Earlier we spoke about the diatonic scale and the fact that it prescribes specific distances that its notes must have from one another, but we didn’t go much deeper than that. The diatonic scale’s distances are specified by using a sequence of large and small steps. A small step is the shortest distance that can be found between two notes on the instrument, On a piano, the smallest step is a white key and its adjacent black key; on a guitar, it would be a fret directly next to another. while a large step is exactly two small steps. The pattern, abbreviating “S” for small and “L” for large, is L–L–S–L–L–L–S. If you follow this pattern on a piano starting from C, you’ll notice that it avoids every black key on the keyboard. C is the only note that does this; starting from any other point will eventually involve a black key.

The song is in F major, whose scale begins and ends on an F note. Following the diatonic scale pattern gives us:

Construction of the F major scale using the standard diatonic sequence. The small circle is a visual aid to highlight the conventional beginning and end of the sequence.

Nothing wrong with that. The scale begins at F and ends at the F one octave higher, and the diatonic pattern repeats the same way for the entire range of human hearing.

The diatonic pattern repeats. The pattern is actually not concerned with starting or ending on any specific pitch. Its primary goal is to ensure that the two small steps are as far apart from each other as possible, maximizing the number of large steps in between. It’s only due to historical conventions that the major scales all start with this particular large step. Does it have to be this way?

What if we shifted our diatonic steps three positions to the right, wrapping the pieces that fall off the right edge onto the start of the pattern? We would end up with L–L–S–L–L–S–L. Or graphically:

Construction of the F major scale with the diatonic sequence starting from its fifth step. Note how the small circle has shifted away from F and over to B♭.

That’s somehow substantially the same, except the E transformed into an E♭, which would be called the flattened seventh (♭7) scale degree when named using F major terminology. It doesn’t really feel like this should be allowed to be called F major anymore. Just going by the notes we ended up with, we produced the members the B♭ major scale—which makes sense, because the conventional “starting point” of the diatonic step sequence moved to B♭ during our little experiment here.

So we have a scale that contains all the notes from the B♭ major scale, but we’re notating and using it as if it were an F major scale. Surely there must be a lofty and inaccessible term to describe this concept. And yup, there sure is: We have constructed a mode called F Mixolydian.

Pulling back, there are seven positions where the diatonic step sequence could be aligned over a scale’s root note, therefore there are seven modes: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. The most common mode for music to use is Ionian, followed by Aeolian for sadder pieces. Mixolydian, it could be argued, is a distant third place compared to the popularity of those other two.

Occasionally you’ll hear people parading around fun facts, for example that “Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd uses the Mixolydian mode. That may be true (or it may not be) but it is not prominently Mixolydian. To be prominent, there should be a distinct and obvious use of the ♭7 note. The chorus of “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” by Beyoncé, that is a Mixolydian section with an obvious ♭7. Come to think of it, I don’t really enjoy “Single Ladies” either. Huh, I guess I’m learning something about myself and my musical tastes on this journey.

Mannheim Steamroller’s “Deck the Halls” is a Mixolydian song with a hit-you-over-the-head ♭7 in the melody. It also spends a whole lot of its time on the ♭VII (E♭ major) chord, rooted firmly at this same characteristic note.

Now, as far as what the motivation was for arranging it in Mixolydian, that’s anybody’s guess.

Hurry up and wait

Let’s take another look at the first line of the melody:

Deck the halls with boughs of holly, Fa la la la la la la la la. Again.

From a standpoint of rhythm and overall timing, this line stretches certain phrases but not others. Compared with the original structure of the song:

Brick chart comparing line 1 of the traditional and Mannheim Steamroller versions. The box marked (r) is a one-beat rest.

Mannheim Steamroller’s version uses a 22-beat line, whereas the traditional song accomplishes the same thing in only 16 beats. The most noticeable effect of this, aside from the song seeming to take a really long time to get the lines out, is that lyrical phrases no longer start and end on a measure divider. And it keeps going:

‘Tis the season to be jolly, Fa la la la la la la la la. (LilyPond source)

This line has 26 beats. Compared to itself from the line immediately before:

Brick chart comparing lines 1 and 2 of the Mannheim Steamroller version.

That is just excessive. It really feels like the song keeps missing its bus transfers and is just standing idly at the corner waiting for the next one to come around. It continually sets up the expectation that the next batch of lyrics is going to come, and then it smashes the expectation by just… not doing it. There isn’t even anything interesting in the spaces added here; it’s just pausing for the sake of pausing.

This makes it extraordinarily difficult to memorize the song. Each line is a special case. You have to pay attention; you have to count. This is “Deck the Halls,” for chrissakes! I’m not counting jack squat! Here’s a fun exercise, assuming you haven’t committed the entire song to memory: Play the Mannheim Steamroller recording, and sing the words along with it. Sing confidently, like you really mean it. See how many times you start singing a phrase in the wrong place. See how unnecessarily hard they made this.

The back half

Continuing on to line three:

Don we now our gay apparel, Fa la la la la la la la la. (LilyPond source)

Structurally, I can’t find much to fault here. Aside from its insistence on adding an empty measure at the end of the line, this faithfully adheres to the rhythm of the original. It’s almost refreshing, in a way.

Of considerable interest is the fact that this portion of the verse contains several E naturals—it is not in Mixolydian during those times. Much like this portion of the original song, this version also contains a brief trip into the key of C Ionian, where the E natural note and the G / Bo chords are more welcome than they would be in F. What’s interesting, and what I’m currently at a loss to explain, is why the B♭ in the third measure remains as a B♭ rather than being raised to B natural along with everything else, but as best I can tell that’s what it’s actually doing.

We’ve come too far to give up now:

Troll the ancient Yuletide carol, Fa la la la la la la la la. (LilyPond source)

Phew, I was getting worried there for a minute that things were getting normal.

Brick chart of the last line of the Mannheim Steamroller verse.

As before, this is yet a third unique line pattern consisting of effectively 20 beats of melody followed by 22 beats of a sustained F, held while waiting for the underlying chords to meander their way back to some semblance of resolution. At least it had the decency to avoid any more E’s or E♭’s.

So let’s stack some bricks and see how decked-out this hall ended up:

Brick chart of a complete Mannheim Steamroller verse.

The structure of this song is just weird. Every line is different from every other line. Self-similar phrases start and end at different places, and there is no way to intuit when a future event is going to occur based on what came previously. You just have to learn each of these pieces individually. I honestly don’t know how the band plays this song live; they must’ve just memorized the bejesus out of it.

The chord progression is no easier. Just as the melody components begin and end in unexpected places, the chord changes similarly follow no easily predictable pattern:

Brick chart of the chords accompanying the Mannheim Steamroller verse. To conserve space, the final IV and I chords, each occupying two complete 4/4 measures, have been compressed.

There is no rhyme or reason to the timing or spacing of the lines in this song. It really feels like this is simply an act of being different for the sake of being different. And if you look at it in a certain light, this might have been the least bad way to perform this cover.

Music criticism; see also subjective nonsense

There are aspects to music criticism that are largely crap. This article especially so. When you get right down to it, enjoying or not enjoying a piece of music says more about the listener than it does about the work itself. This song has every right to exist, and the people who enjoy listening to it are entitled to feel that way. Anybody can cherry-pick details to focus on while backing their claims up with fancy graphs and academic footnotes, but it does not make them objectively right. There is no such thing as being objectively right in artistic endeavors.

At the same time, however, it can sometimes be absolutely mystifying to think about why certain things achieved their popularity. Of all the things that could’ve found an audience, all the things that could’ve resonated with consumers, these things that we collectively choose to buy and hang onto and cherish for decades or even generations, why “this” instead of any other “that?” We can’t answer that either; it requires some metric of absolute truth that just doesn’t exist. Sometimes it really is just pure happenstance, a stroke of dumb luck from a random universe.

And that’s the shortcoming of a lot of critical writing: When done poorly, it is a reviewer’s personal opinion masquerading as some kind of statement of fundamental truth. We all have things we like and things we don’t. A select few people have been granted a magazine column or a podcast audience, but that doesn’t automatically mean the columnist or the host has any sort of innate truth-seeking power that nobody else was blessed with. I kinda liked Chinese Democracy. I hated 90% of Random Access Memories. Were the reviewers wrong? Was I wrong? The answer to both is most likely no; we are just different. We are all free to feel ways about things.

I don’t like the Mannheim Steamroller version of “Deck the Halls” because it is simultaneously too close to the traditional arrangement of the song while also being too different from it. This is an absurd duality, and I’m frankly impressed that I managed to back myself into this corner with it. But fundamentally, that is what I believe. Almost every note of the melody is exactly what the traditional arrangement uses, except for a pair of notes that are so unabashedly Mixolydian that I find myself unable to tune them out whenever they pop up. At the same time, I’m frustrated by the unusual and difficult-to-predict chord progressions and rhythmic changes. I desperately want it to sound like the “Deck the Halls” that we all sang at our fifth grade holiday concert.

And yet, were I to get what I think I want—Mannheim Steamroller playing a bog-standard sixteen-bar “Deck the Halls” in Ionian, with a couple of synthesizer licks and maybe a harpsichord or something buried down in the mix—I would probably think that was a cheap and lazy cover that didn’t bring anything new to the table aside from a couple of unjustifiable beeps and boops. It would be boring. And that’s my best guess as to what led Chip Davis to arrange the song the way he did: If he didn’t mix up the composition and violate the listener’s expectations with it, what justification would there have been to record it in the first place?

I really don’t know what intentions Davis and the rest of the band had when they made this. I have not found any interviews or discussions that really shed any light on what their work is supposed to mean, if it means anything at all. It may have just been an exercise in arbitrary self-indulgence, or it may have been a deeply calculated homage to something so obscure and deeply guarded by its creator that we may never grasp the full picture. Unless they come out and state it plainly, we’ll never know. And even if they did, some of us would probably choose to ignore it anyway.

I analyzed two songs here, the traditional version and the Mannheim Steamroller version. There is no need to try to change the latter into the former, because the former already exists. Rather than listening to a version that I don’t prefer, there are dozens of other versions that I could listen to instead. Whenever others proclaim that they like the Mannheim Steamroller version of this song and I wonder how on earth such a thing could be possible, I just have to remind myself that we are different people and we prefer different things. I’d like to think I’m starting to get better at that. I still kinda wish they would find something else to play over the store’s speakers, though. Ah well, it’ll be over in three minutes.

“Sing we joyous, all together […] Heedless of the wind and weather.”

« Back to Articles